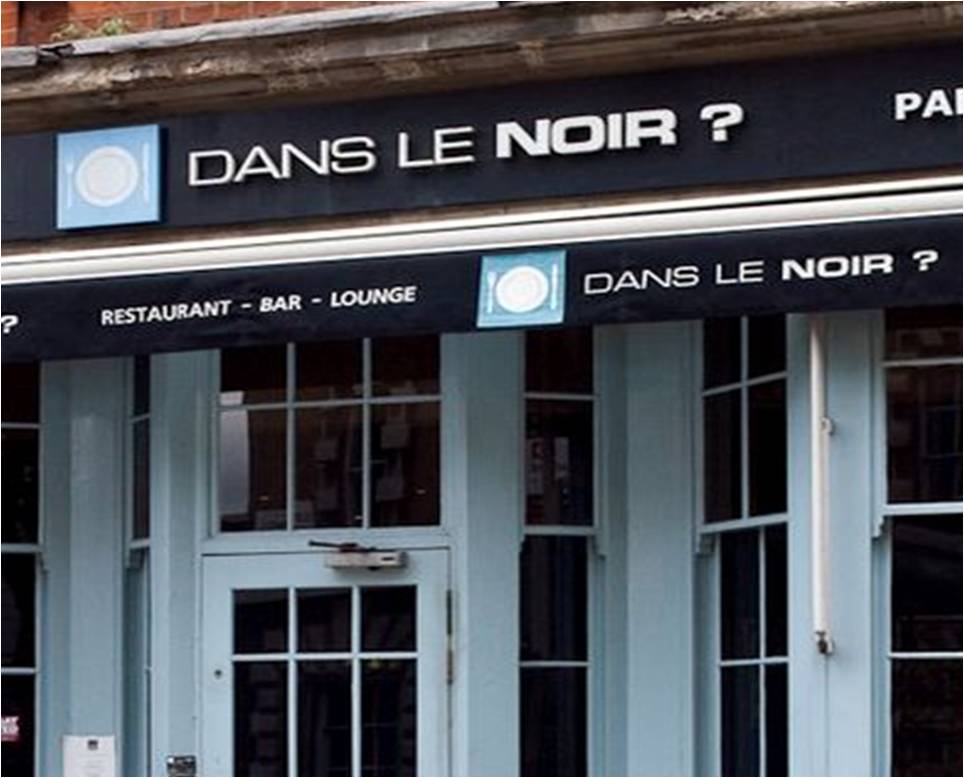

Once upon a time, not so long ago, I went on a blind date, literally. I arrived early, contrary to expectations. My friends and I had been looking forward to it forever and being late was definitely not an option. The restaurant, aptly named 'Dans le noir?', was reputable not just for its culinary expertise, but more importantly for the peculiar nature of the services it provides which are designed to challenge the senses. I did not want to miss any part of the experience.

It turned out that the restaurant had one golden rule: "No lights allowed in the dining area" - so no phones or any other light-emitting devices. Just before being ushered into the dining area, we were reminded of this rule and then entrusted in the care of a very lively female guide. I didn't quite get what the whole fuss about the "no light" rule was until we were led through a progressively darkening corridor into a "black void."

The darkness was so thick I could cut through it with a knife. I opened my eyes as wide as I safely could without popping them out of their sockets but I still could not make out a single thing. I kept on thinking that my eyes would adjust to the environment and I would be able to see something, no matter how little. But ... nothing.

I tried pinching myself but the pain of my finger nails digging into my flesh assured me that I was certainly wide awake. I felt myself drowning in a wave of panic and claustrophobia, but just when I was about to let out a scream, I was saved from imminent embarrassment by the reassuring voice of our guide somewhere down the human chain we had formed. She seemed to be in full control of the situation so I clung onto it like a beacon of hope. All I could think of was "Don't lose your guide."

She skillfully herded us through what seemed like a mace. The place must have been quite full because I could overhear the conversations of the other diners. After what seemed like an eternity, we miraculously made it to our tables without bumping into anything or anyone. She deftly got us all seated and pointed out where everything was- cutlery, plates, glasses.

Our initial self-consciousness soon gave way to a relaxed atmosphere. After all, no one could see if you were eating with your fingers or if you had sauce dripping all over your chin. We had a hilarious time trying to figure out what the different components of the meal were based solely on touch, taste and smell. We were so loud that someone (I have no idea who) pointed out that we could actually hear one another just fine without having to shout.

Almost everything had a different taste and consistency from what I was used to. I think it was best for my peace of mind that I didn't know for sure what I was eating, judging by some of the weird suggestions that were coming up. I imagined the spectacle we would have created if we had been feasting on some local (Nigerian) delicacies such as pounded yam with thick, slimy okra or ogbono soup. Delicious, no doubt; but messy would have been an understatement.

Two hours later, we were still at it, reluctant to leave, a certain inertia enticing us into staying longer than was reasonably decent. We had had so much fun and I felt exhilarated, like I could do anything, perhaps even outrun Usain Bolt! (wishful thinking). When we eventually emerged into the "light", I was relieved to find that I didn't have any funny food stains on my clothes. But I wasn't the only one discreetly checking!

On my way home that night, I couldn't help but wonder what life would have been if that two-hour experience had not been temporary; what it would be like to live in a world, constantly enveloped in a curtain of impenetrable or near total darkness. For our pretty guide and most of her colleagues, as well as some 36 other million people around the world, that is their reality.

However, through creativity, something that might have been perceived as a disability, has been transformed into a profitable, awe-inspiring experience which forces diners to "rely on other senses" and "neatly inverts the usual relationship between the blind and the sighted."

Disability is a chameleon with many faces, sometimes subtle, sometimes pronounced, and we are all victims, one way or the other. But as C.S. Lewis succinctly puts it, "every disability conceals a vocation if only we can find it, which will turn the necessity to glorious gain".

Don't let what you CAN'T do interfere with what you CAN do (John Wooden).